Sam Chambers October 10, 2022

Assessing where the rates floor is in the consolidated container shipping market is keeping experts busy as multiple indices continue to report steep declines.

UK consultants Drewry last week lowered its demand outlook for 2022 to 1.5%, and to 1.9% for 2023 on the back of heavily downgraded GDP predictions.

“Carriers will have accepted that prices and profits were unsustainable,” Drewry suggested, going on to state that carriers would start cutting back when rates sink close to a level that would be acceptable in the long run. “Recent news of more East-West service suspensions, including a 2M Transpacific loop, indicates that time is now,” Drewry stated, predicting that the next course of defensive action would be to offload older, gas-guzzling ships with 2023 likely to see near-record volumes of boxship demolitions, while a number of the huge swathe of newbuilds ordered will be deferred.

What level of profitability will the carriers balk at lowering their sales revenues?

Despite these measures, Drewry reckons they will be insufficient to fully bridge the supply-demand gap next year, with an estimated net increase in effective capacity of 11.3%, way above the projected demand growth of 1.9%. Adding in missed sailings will get them closer and should be enough to keep freight rates and profits above 2019 levels, Drewry is forecasting.

“The question should not be what is the new normal for the rates, but at what level of profitability will the carriers balk at lowering their sales revenues?” argued Kris Kosmala in conversation with Splash today.

Kosmala, a regular Splash columnist, said that carriers have got better at aligning capacity with demand at a more granular level than they were able to do in the past, a dividend of their investments in better analytics technology.

“Historically, during the ‘steady as she goes’ periods, the average profitability for the industry was about 10%,” Kosmala observed, going on to forecast: “Let’s assume this is the comfort level the shipping carriers are willing to live with. That’s a very long descent path from the 70+% results seen today, but that means the rates will be allowed to drop for some time yet. When you see the industry start reporting profitability between 10 to 20%, the rates we will see at that time will become the new normal”.

Parash Jain, HSBC’s global head of shipping and ports research, has repeatedly maintained that liner shipping now has a stronger bargaining position thanks to consolidation.

“Going forward, we argue that after years of consolidation and the formation of mega shipping alliances, the shipping lines have learnt the capacity discipline and while there might still be volatility in freight rates, the rock-bottom level of freight rates seen in the past decade might no longer persist in the future,” Jain told Splash in a report published earlier this year.

The consolidated nature of global liner shipping, where the top liners control more than 85% of capacity, was also brought up by shipping analysts at Jefferies in a recent report, who argued that their ability to move in a far more bigger fashion gives them the chance to make quick supply responses. This was most visible in 2020 when liners idled as much as 13% of vessel capacity, which supported freight rates and allowed for profitable earnings despite the significant slowdown in market activity during the first few months of the pandemic.

The swiftness and severity of the container drop in fortunes has also been analysed by Clarksons Research.

Faced with significant macroeconomic headwinds and surging inflation for consumers, container trade has faltered, down by 1.6% year-on-year from January to August, whilst since July container port congestion has reduced according to Clarksons, from close to 38% of capacity at port to around 34% today, freeing some of the tied-up tonnage.

“Sentiment has weakened at a rapid rate, amplified by increased uncertainty for consumers and businesses,” Clarksons noted in a recent market report, stressing that today’s rates still remain well above pre-covid levels. Freight is twice as high as the 2019 average, charter rates are still two and a half times higher, while the the Shanghai Containerised Freight Index (SCFI) is 100% above the 2010 to 2019 average and Clarksons’ charter rate index is only 20% off the 2005 peaks in the previous boom.

“In a ‘base case’ rate levels might not fall back as far as previous lows, but watch closely for incoming fleet growth (6-8% p.a. in 2023-24, though slippage may impact), ongoing trade headwinds and the development of port congestion (will recent easing persist?) which will determine how far and fast the softening goes from now,” analysts at Clarksons advised.

Container Trade Statistics (CTS) has released the new global demand data for August 2022, which has turned out to be the weakest month since early 2020.

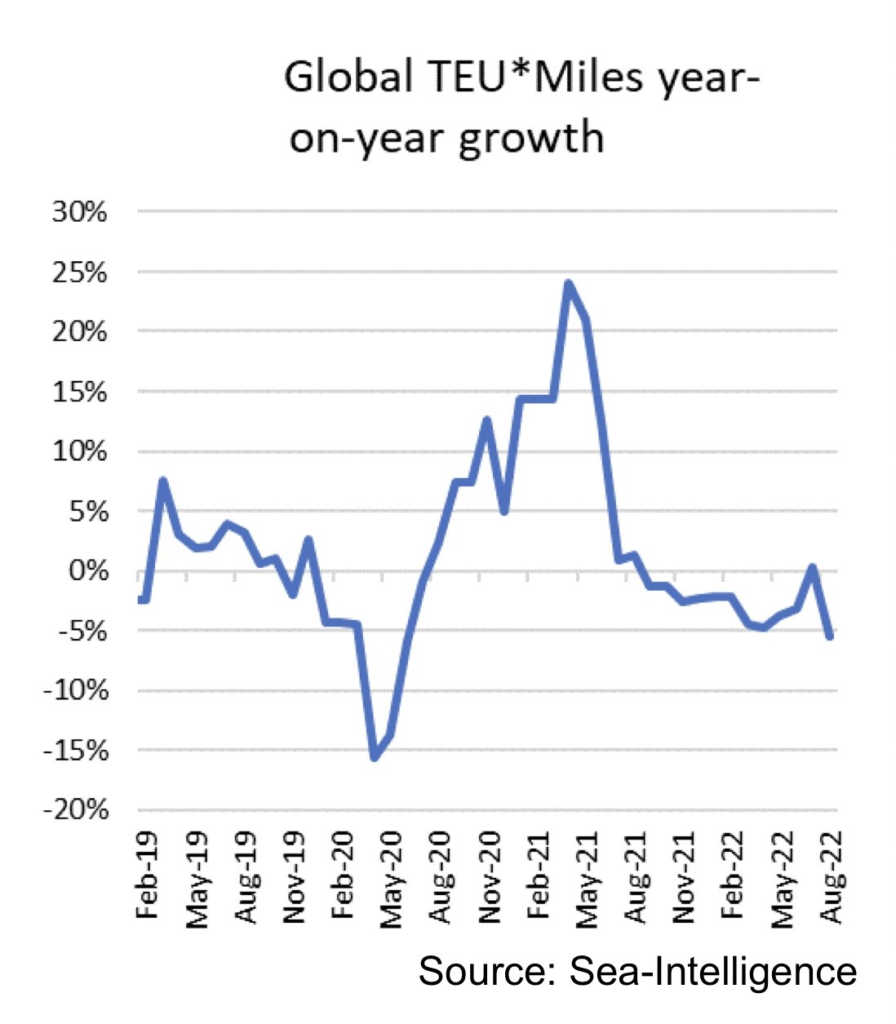

Global demand measured in teu declined by 4.2% year-on-year whereas demand measured in teu*miles declined by 5.5%. Compared to pre-pandemic August 2019, global demand in teu has grown 1.3% whereas demand in teu*miles has now declined 2% compared to August 2019.

Looking at the CTS figures, Lars Jensen, CEO of consultancy Vespucci Maritime, suggested via LinkedIn that from a fundamental global supply/demand perspective, there is no longer a fleet capacity shortage and the balance is poised to worsen further.

“This means there is no fundamental support to revert back to the high rates of the last two years, but also that there is no structural support to halt the current rate decline,” Jensen wrote.

“Global demand is clearly weakening and weakening quite rapidly. We should expect continuing declines in spot rates – and associated spill-over into the contract markets. And we should also expect a ramp-up in not only blank sailings, but also the complete closure of a range of services, on especially the Transpacific trade,” Sea-Intelligence warned in its latest weekly report.

Drewry’s World Container Index (WCI), a global spot rate reference, plunged below $4,000 per feu last week for the first time since December 2020, with most container indices – whether spot, long-term, or charter, on the slide in recent months. The WCI dropped another 8% last week to close on $3,688.75, still more than twice as high as the historical average, but a far cry from the $9,408.81 per feu registered at the start of this year.

Multiple chartering indices have continued to report steep drops in recent days.

“The temperature is dropping fast, not only in Northern Europe but also in the container chartering market and consequently the New ConTex Indices are all bathed in red,” the latest report from Hamburg’s New ConTex stated.